Space data centers sound wild, but they aren’t pure sci-fi. The upside is steady solar power and no real estate fights. The downside is latency, cooling by radiation only, space junk, and licensing. If this happens, it likely starts with niche, batch-oriented workloads in low Earth orbit, then scales cautiously.

What did Bezos actually say?

At Italian Tech Week, Jeff Bezos said building gigawatt-scale data centers in space might be feasible in 10 to 20 years, mostly because space offers continuous solar power and avoids land and water constraints on Earth. He also warned against hype while staying optimistic. Timeline aside, it’s a “maybe,” not a promise.

Table of Contents

What is a “space data center”?

Think of it as an orbital compute platform. You launch modular racks that host compute and storage, connect them via satellite links, power them with solar arrays or nuclear sources, and reject heat with radiators. Data moves up and down through ground stations or inter-satellite links.

Why space looks attractive

Power and uptime. Space offers near-continuous sunlight if you choose the right orbit and panel orientation. On Earth, data centers are already straining grids and water supplies. If demand keeps rising with AI, pushing some capacity off-planet starts to look tempting.

Land and siting. Permitting and NIMBY concerns slow big campuses. An orbital facility avoids land and water permits. You still pay for launch, integration, and traffic rights, but you’re not fighting for substation capacity near a metro.

The hard parts no one can skip

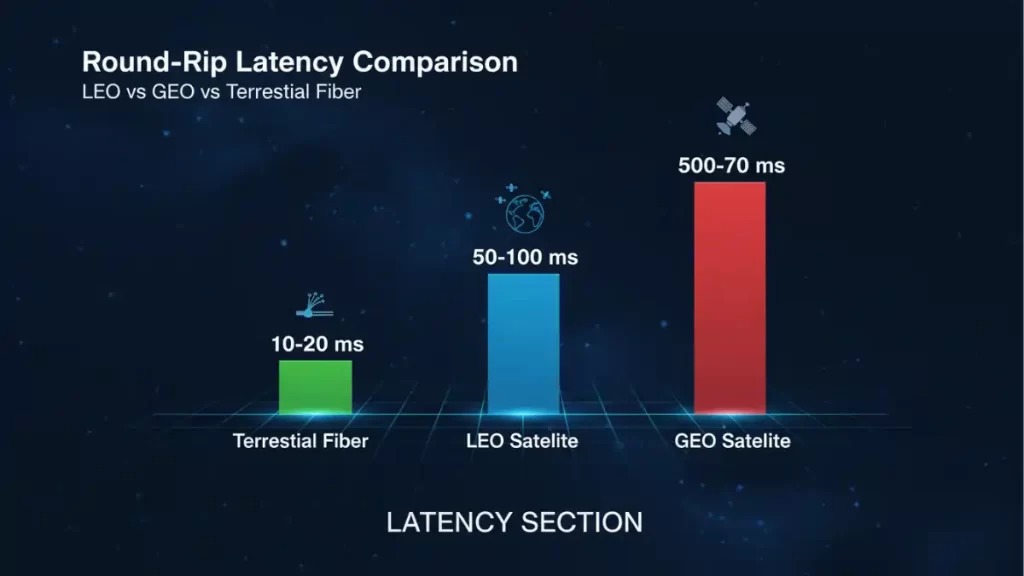

Latency. Distance matters. Low Earth orbit (LEO) can deliver tens of milliseconds round-trip. Geostationary orbit (GEO) is hundreds of milliseconds. That’s fine for batch jobs and cold storage, but not for interactive cloud or gaming. Expect early use cases to be AI training checkpoints, video rendering, backups, and scientific workloads where delay doesn’t hurt.

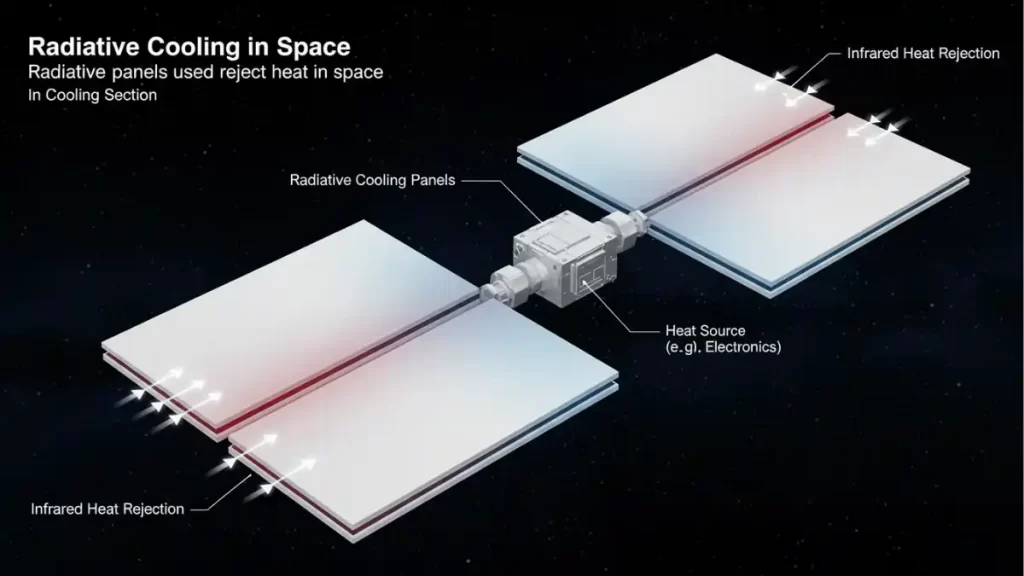

Cooling in a vacuum. Space is “cold,” but that doesn’t cool your chips. There’s no air to blow heat into. You must radiate heat away, which means big, lightweight radiators and careful thermal design. This is solvable, just not trivial, and it adds mass and complexity.

Maintenance and risk. If something breaks, you can’t roll a truck. You design for redundancy, robotic swaps, and short lifetimes. You also follow debris guidelines, coordinate spectrum, and register with regulators. The policy work is as real as the engineering.

A practical roadmap: from demo to scale

- Pilot a small LEO “compute pod” tethered to a few ground stations. Run batch inference, video transcoding, or backups.

- Thermal prove-out with deployable radiators and liquid loops. Instrument the heck out of it.

- Networking via inter-satellite links to move data in space before dropping it down near users.

- Ops model for on-orbit servicing: robotic replacement, modular panels, planned deorbit.

- Scale to a cluster and add dedicated energy (larger arrays or nuclear) once utilization justifies the mass.

Quick pros and cons

| Factor | Space data centers | Earth data centers |

|---|---|---|

| Power | Near-constant solar in certain orbits | Grid constraints; PPAs; curtailment |

| Latency | LEO tens of ms; GEO hundreds of ms | Fiber <10 ms metro; ~50–100 ms inter-city |

| Cooling | Radiators only; design heavy | Air/liquid; water and siting limits |

| Land/Permits | None in orbit | Land, water, permits, neighbors |

| Ops | Hard maintenance; robotics | Mature supply chains, easy swap-outs |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Are space data centers realistic?

Possibly, for specific tasks. Expect pilots this decade, scaled use only if economics pencil out.

Which workloads fit?

Batch AI, rendering, DR backups, astronomy pipelines, data staging for downlink.

Will they be “green”?

Power can be clean in orbit, but launch emissions and radiator mass matter. Net impact depends on design and cadence.

What about debris?

Operators must meet debris mitigation rules and design for deorbit. Risk is manageable but non-zero.

Featured Snippet Boxes

What is a space data center?

An orbital compute facility that hosts servers in space, powered by solar or nuclear sources, cooled by radiators, and connected via satellite links. It targets batch or delay-tolerant workloads first.

Why consider data centers in space?

Continuous solar power, no land or water permits, and potential to offload grid pressure. It may help specific workloads if mass, cooling, and network costs are tamed.

How much latency would users see?

LEO can deliver tens of milliseconds round-trip; GEO is typically 500–700 ms. Good for batch jobs; poor for real-time apps.

What’s the toughest engineering problem?

Thermal management. In vacuum you can’t convect heat; you must radiate it away, so radiator design and mass dominate.

When could this arrive?

Optimists say 10–20 years for meaningful capacity. Expect demonstrations first, then cautious scaling.